Paul McCartneys nyårslöfte inför 2025 – ett nytt album!

Paul McCartney svarar på sin hemsida om ett nyårslöfte för 2025

Skulle det bli lite lugnare på Beatlesfronten under 2025? Knappast!

På frågan från ett fan om Paul McCartney har några nyårslöften för 2025, svarade han på sin hemsida så här:

So, I’m hoping to get back into that and finish up a lot of these songs.

So, how’s about that? ‘My New Year’s resolution is to finish a new album!’

How about that for a teaser?

Paul McCartney besvarar frågor från fansen på sin hemsida.

Paul McCartneys senaste soloalbum var McCartney III, som släppts den 18 december 2020 – som uppföljare till albumen McCartney från 1970 och McCartney II från 1980.

Vad som är känt i nuläget, så har Paul McCartney inte några framträdanden inbokade för 2025. Men han avslutade den sista konserten i London den 19 december 2024 med att säga See you next time.

Om vi känner Paul rätt, och det gör vi ju, eller hur, så vill han säkert ge sig ut på någon form av turné även under 2025. Han kan ju vare sig sluta spela inför publik eller skriva nya låtar. En musikalisk workaholic!

The Beatles – Detta händer den 27 december 1967

Paul McCartney intervjuas av David Frost om ’Magical Mystery Tour’

Dagen efter Boxing Day och BBC1:s visning av tv-filmen Magical Mystery Tour gav Paul McCartney denna onsdag en tv-intervju för David Frost.

Efter det att såväl kritiker som tittare gärna påpekade att detta var The Beatles första artistiska misslyckande ville Paul McCartney förklara gruppens skapelse.

Intervjun ägde rum i The Frost Programme, som spelades in inför en studiopublik vid Associated-Rediffusions Wembley Studios mellan kl. 18.00 och kl. 19.00. Programmet sändes sedan samma kväll mellan kl. 22.30 och kl. 23.15.Frosts konversation med McCartney upptog första halvan av programtiden.

The Beatles’ music brings unanimous enthusiasm and approval pretty well. Last night their television show did not bring unanimous enthusiasm and approval, and everyone seems to be discussing it today. Here is the man most responsible, Mr Paul McCartney.

Paul McCartney:

Good evening, Mr Frost.

David Frost:

Good evening, Mr McCartney. Why don’t you think that the critics liked this film?

Paul McCartney:

I don’t know, you know. They just didn’t seem to like it. I quite liked it myself.

David Frost:

Well, I liked it. I didn’t see it last night because I was busy, but I saw it today, and I liked it… I mean, with reservations and so on. But why were people so puzzled by it?

Paul McCartney:

I think they thought it was ‘bitty,’ which it was a bit. You know, but it was supposed to be like that. I think a lot of people were looking for a plot, and there wasn’t one.

David Frost:

I saw it in colour. That sort of helped, too.

Paul McCartney:

We thought we could just do a thing… See, we’ve been waiting for a couple of years now to make another feature film. And we’ve been asking people to write stories and write plots. But nobody’s come up with one, you know. So we thought, ‘We’ll do something which isn’t like that,’ which isn’t like a real film in as much as it’s got a story and a beginning, and we’ll just do a selection of, you know… We’d put together a lot of things that we like the look of, and see what happens. I liked it.

David Frost:

Did you have a point in mind when you, I mean, some point to get across at all when you did this?

Paul McCartney:

No. See, that’s the trouble, seriously. You gotta do everything with a point or an aim, but we tried this one without anything, with no point and no aim. It’s like, you know, we make a record album and all the songs don’t necessarily have to fit in with each other, you know. They’re just a selection of songs. But when you go to make a film, I don’t know, you seem to have to have a thread to pull it all together. We thought that doing a mystery tour, you know – it’s all happening on a bus to this group of people – would be enough of a thread. And then, calling it a magical mystery tour, which – like a firm advertises a magical mystery tour, and you go on it, and it really is magic – then anything might happen, and it wouldn’t have a thread if it was magic.

David Frost:

What’s the difference between what you were trying to do here, and say, if you took an EP – which most people have of Magical Mystery Tour – and played that while looking at a kaleidoscope?

Paul McCartney:

Yeah.

David Frost:

What’s the difference between that and what you did? I mean, was that what you were trying to do?

Paul McCartney:

That’s the thing, you know, that there’s no real difference between that – except that we had people in the kaleidoscope, and we had things happening. But, I mean, it’s not really all that disconnected. The trouble is, that, er, if you watch it a second time it does grow on you. And this is one thing we forgot, because when you make a record, a lot of people listen to our records and say, ‘Well, I don’t like that one,’ you know. But the second time ’round they say, ‘Not bad.’ And after a few plays they say…

David Frost:

Well, now the BBC are going to show it seventeen times. Just sign the thing today.

Paul McCartney:

Yeah!

David Frost:

Is the fact that it didn’t get across to a lot of people, does that fact alter your opinion of it? Do you say, ‘Right. It seems to have failed?’ Or do you still think it’s precisely as good as if people had said it was very good?

Paul McCartney:

Yeah. I think it’s as good as I always thought it was. But when we were making it, I think all of us thought, ‘This has got a very thin plot. We hope this idea of doing a thing without a plot works, because the one thing we’re gonna be able to say is, it hasn’t got a plot.’ But yeah. We thought, ‘You don’t need a plot. You don’t always need one.’ Because, like, the things you did today probably didn’t have much of a plot.

David Frost:

Oh, I was plotting all day. But no, I can see it. Would you call it a success or a failure today?

Paul McCartney:

Er, it’s both. You know, it’s a success failure. You can’t say it was a success, you know, ’cause the papers didn’t like it. And that seems to be what people read to find out what’s a success. But I think it’s alright. I think the next one will be a lot better, and it will have a fat plot, as opposed to a thin plot.

David Frost:

But, I mean, what is success then? How would you define that?

Paul McCartney:

I don’t know. I wouldn’t try. I suppose, you know, I don’t know how many people liked it who saw it.

David Frost:

How many people here liked it?

Paul McCartney:

There’s a few, you know. It wasn’t much of a success!

David Frost:

They like you much more than they liked it, you see. But I mean, [to the audience] you better watch it again and again on BBC.

Paul McCartney:

Seventeen times.

David Frost:

Can it be a success when people don’t like it?

Paul McCartney:

It obviously matters. If this morning, we’d awoke to find fantastic reviews then we would have all said, ‘It’s a success.’ And I wouldn’t have been on tonight, David. But it doesn’t matter all that much, ’cause people said about two of our records, like ’Strawbverry Fields Forever’ och ’I Am The Walrus ’ to name but two. They said, ‘Those are terrible,’ you know, ‘You can’t talk about let your knickers down on telly. You can’t do it.’ But you can, you know. I’ve just done it! And it’s alright, you know. Because, in about a year or two, these things that didn’t look like successes will look a bit more like successes… you know, as people get into that kind of thing.

You said today, somewhere, that if this first film that you made yourselves had been a rave, then there wouldn’t have been a point in doing any more. What did you mean?Paul McCartney:

There would have been a point, but it wouldn’t have been as much of a challenge to do the next one. At least now we know that we’ve got not all that much to live up to.David Frost:

How often do you have a message, actually? Do you often say, ‘I hope a point gets across to people out there’?Paul McCartney:

Umm, no. I never say that. But everything has a message, but you can’t just pick out one little thing and say, ‘Is that their message?’ You know, everything we do is never intended to have a great deep message, but it has. Like everything you do, like everything everybody does.David Frost:

Like whe John and George were talking about the Maharishi, they were saying that the main sort of point of his massage was ‘Know thy self,’ and so on. Is that what you…Paul McCartney:

It’s got to be. It’s the only point in anything anybody does ever, if you just get to know what it is you’re doing. We don’t do it deliberately, like ‘OK, we gotta get this message over in our songs.’ We just do songs. But if you ask the question about the message, I think there is one there. I still don’t know what it is.David Frost:

It’s there, but you don’t know what it is.Paul McCartney:

But I’m trying!David Frost:

By the 17th time…PAUL:

…I should know. Yeah.David Frost:

When you approach something like this, do you all equally feel the same sort of thing, like, do you all have a sort of kinship of feeling about the Maharishi? Or about the approach to this film, for instance? Or do you all not?Paul McCartney:

No. Like any four people it varies. We don’t all exactly feel the same thing. It’s pretty near, though, that’s why we’ve kept going as we have, you know? Because we happen to be pals, so we’ve got nearly the same kind of attitudes about most things.David Frost:

How do you categorise yourself? I mean, people think of Ringo as the clown, and George as the sort of mystic, and John as the rebel. What would you come out as?Paul McCartney:

Oh. I don’t know. (pause) I keep hearing that I am ‘the cute one.’ I don’t know.David Frost:

You’ve had five years of all this, now, looking at everything from a very special vantage point. Do you, in general, sort of respect the human race more now, having seen it close range in this way for five years?Paul McCartney:

Yeah. Of course, you know. The human race is fantastic, but what the human race does, I’m not always so keen on that as I used to be.David Frost:

How do you mean?Paul McCartney:

Well, the human race does some fantastic things, and that’s another programme.

David Frost:

Well, we’ll get it into this one.

Paul McCartney:

OK, well, you know the kind of thing I mean. Before you come into showbiz, you tend to think ‘It’s great, it’s fantastic,’ and ‘That’s my aim in life is to be rich and famous,’ and you can’t see much more beyond that, you know. But, once you’re rich and famous, you start to wonder what it is you’re actually doing. It can be disappointing if you suddenly realise that everyone is fighting and everyone is messing it up generally, for themselves, folks. I don’t blame ya ’cause I do it too. But we got to get together on this thing, David.

David Frost:

What did you decide, when you were rich and famous, was the point of what you were doing?

Paul McCartney:

The point? I can’t see a point. I think the point is just to do it to the best of your ability. Do it as best as you can, you know, and to try and help. That’s the only point I can see is just to try and help yourself and others. It sounds very christian, and it is.

David Frost:

What are people doing to ‘mess things up’?

Paul McCartney:

For a kickoff, people still believe that thing about ‘We gotta fight, because if we don’t fight, they’ll fight us.’ And so everyone keeps the myth of war going. It’s a bit silly because they’re killing each other off and fighting and shooting. And then, all the little follow-ups to that kind of thought.

David Frost:

It always strikes me that, while you’re associated with all these new movements that come up, or whether people call them Flower Power, or whatever, that you, particularly, tend to become impatient with simplified vague explanations, like the phrase ‘Make love not war,’ for instance.

Paul McCartney:

I don’t mind the slogans that come out of it as long as they’re good ones, like ‘Make love not war.’ It is over-simplified, but slogans have to be.

David Frost:

To what extent do you feel responsible for the effects that you can have on people in the sense that they’ll do what you say? I mean, the obvious example is when you say something about LSD or something, people are slightly more likely to do what you say.

Paul McCartney:

I don’t feel responsible because I’m always a bit suspicious of people who say they’re responsible, because they’re not really straight ordinary people. It always seems to be a politician getting up and saying ‘These boys are responsible for the nations morals.’ And he says ‘I am, and we’ll do our best when we get in if you’ll let us.’ And when they get in, they don’t. And they’re not really responsible. People that say they’re responsible always cop out on responsibility. So I don’t feel really responsible. But at the same time I don’t want to hinder things.

David Frost:

For instance, when you said the thing, I know it’s months old…

Paul McCartney:

No no, these people – they asked me. You know, that was the trouble. They said to me, ‘Have you ever had LSD?’ And I said, ‘Er, yes.’ And that was it, you know. And it was a big newspaper story, and I was made to look as though I’d said to the whole nation, ‘Take LSD,’ you know. And I haven’t. I just said, ‘Yes, I’ve taken it.’ And, er, maybe it would’ve been better if I’d said, ‘No, I haven’t.’ But maybe it would have also been better if they hadn’t have asked me.

David Frost:

Right. And what would you say now to the young people in this audience about drugs?

Paul McCartney:

Don’t bother, you know. There’s not much point. There’s no need for drugs, but there’s no need for a lot of things. There’s no need for alcohol either, and you know, it goes on and on. You can’t just say drugs, because when you say drugs you gotta say ‘And also don’t drink whiskey,’ and you sound like one of these fellas who says it! And I’m not, you know.

David Frost:

Is there anything else that, if you ran into some of your contemporaries in Liverpool, is there anything with the fantastically special life you’ve had in the last five years that you’ve learned that you could tell them, that they might not realise about?

Paul McCartney:

Umm… I don’t know, really. There’s a lot of hints I could offer. I don’t know whether they’d take ’em, because I don’t think I’d have ever taken ’em. Hints about if you’re trying to make money. A lot of people don’t realise how easy it is, because a lot of people work there, with the boss there, and they’re satisfied to do that.

David Frost:

How is it easy to make money?

Paul McCartney:

Well, you know.

David Frost:

But, I mean, I wouldn’t have said ‘easy.’ That’s the difference.

Paul McCartney:

I think that I always found it difficult to make money when I wasn’t being myself. I really found it – ’cause I was being the fella in that position – that’s what I thought I had to be. But I never realised that, in fact, you want the fella in this position to be himself, and not to say ‘Yes, that’s jolly good.’ You want him to say, ‘Well look, I’ve got a good idea for this.’

David Frost:

Yeah, but are bosses as lovely as that?

Paul McCartney:

No. And that brings you to good bosses, because they should do the same thing. They don’t realise it either.

David Frost:

The difference is that you and I are in areas like television or music or whatever where there isn’t a great organization and a great system, and sort of individual people with ideas that lead to the way for them to express their ideas. But there may not be that in, for instance, the police force or in the garment industry.

Paul McCartney:

Yeah, well, OK. I can only speak for my bit of it. I can tell them how to make money in entertainment.

David Frost:

What about the rest? Anything else other than the money side?

Paul McCartney:

Right now, the only advice is the one that I’ve always had: to always be meself.

David Frost:

And another thing: you don’t take advice, do you? I mean, you…

Paul McCartney:

Well, because the advice is often to not be yourself, you know. It’s like the show last night. The advice really, if we had taken it, after today’s Trib would’ve been, ‘You get a good choreographer, lads. A good director, producer. And get a lot of money behind ya, and we’ll have 5,000 dancing girls, and we’ll have you hanging from a Christmas tree. And it’ll be great because it’ll be…’ and it’s true, it would have been safe and set and everything. But we thought ‘We’ll try it our way, and if it doesn’t work…’ It doesn’t matter too much that it wasn’t the success that we’d hoped, you know, for that reason. Because still, at least we were able to be ourselves. And do what we thought was right.

David Frost:

And what you think is right, next time, may be different as a result of this experience.

Paul McCartney:

Yeah, but that’s the only way you can learn, you know. If we’d learned by putting ourselves in someone else’s hands and then letting them say, ‘We’ve got to do the vaudeville here, then it isn’t us doing it. And that’s the point of what we’ve done. You know, we’ve always just made records according to how we thought they should have been made, and alot of people said, ‘Well, that’s not the way they’re doing it now.’ And we said, “We’ll carry on and do ’em like this, and see if you like ’em when you get used to ’em.’ And it’s worked.

Några kommentarer från några andra som var med när filmen gjordes:

Paul McCartney:

Vi spelade in filmen i färg men den sändes på BBC 1 i svartvitt. Det var hela avsnitt som helt enkelt var obegripliga på grund av detta. Jag såg den på tv och den såg galen ut i svartvitt eftersom det fanns delar i filmen där färgerna ändrades. Så det blev lite dumt.”

George Martin:

BBC 1 hade inte färgtäckning vid den tiden.

Tony Barrow:

Det är absurt, men filmen sändes i svartvitt. Mycket av filmens dragningskraft ligger i de färgglada kostymerna och sceneriet.

Neil Aspinall:

Det var en flygscen: molnen ändrar färg till en vacker melodi. Men ingen såg detta svart på vitt. Därför förstår jag publiken som undrade: ”Vad är det här?” De var besvikna över vad de såg.”

Ringo Starr:

Som brittiskt beslutade vi att vi skulle ge det till BBC, som på den tiden var det största tv-nätverket, men de visade det svart på vitt. Vi var dumma, och de var dumma. De hatade filmen. Alla hade möjlighet att säga: ”De har gått för långt. Vilka tror de att de är? Vad betyder allt detta? Det var som en rockoperasituation: ”Det här är inte Beethoven.” Alla letade efter något som var vettigt, och filmen var ganska abstrakt.

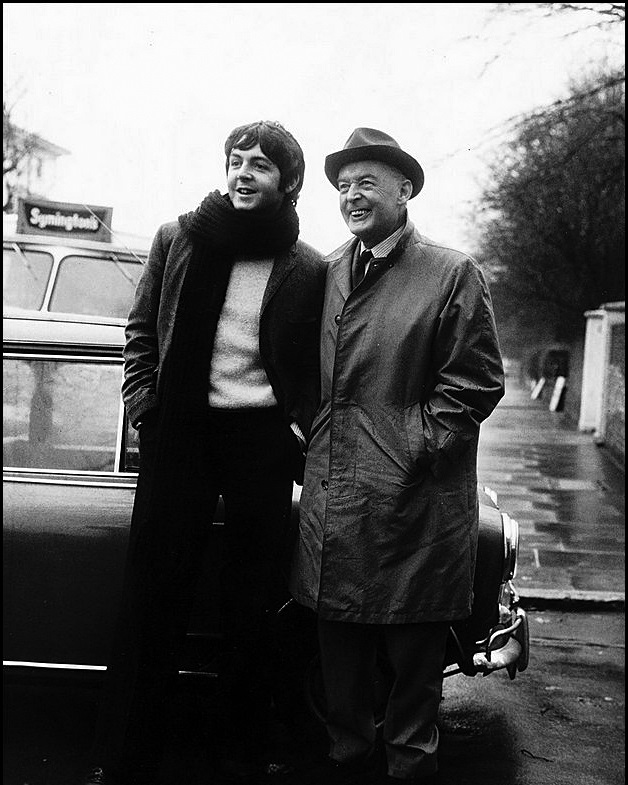

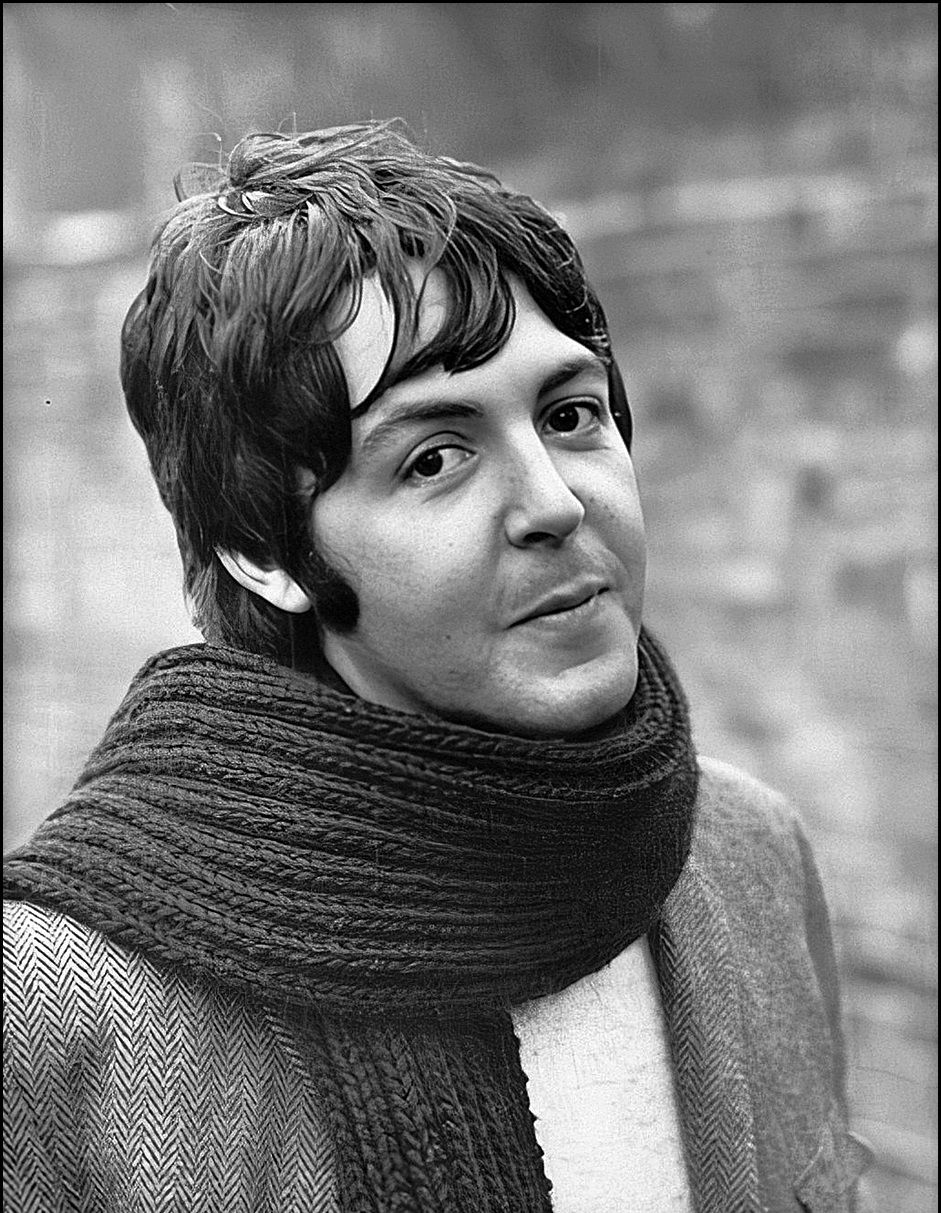

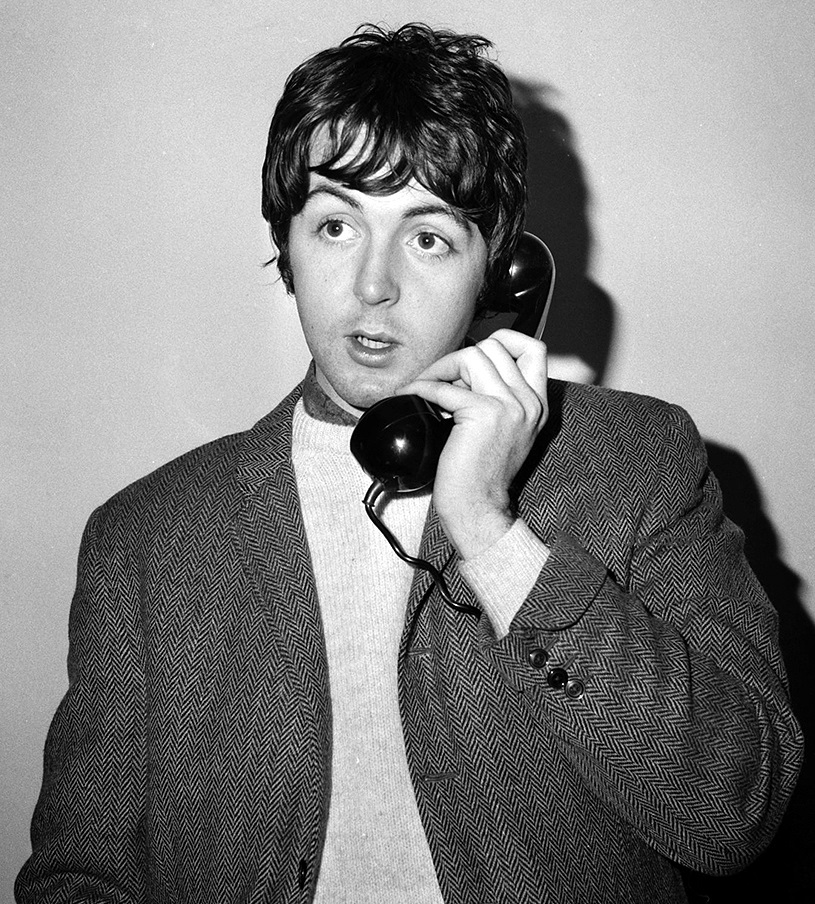

Paul McCartney intervjuas av Ray Connolly i sitt hem på Cavendish Avenue

Paul McCartney tillsammans med sin far James McCartney

utanför Pauls hus på Cavendish Avenue nr 7.

trots all kritik för filmen ’Magical Mystery Tour’.

tillsammans med sin något undrande hund.

James McCartney lyssnar på vad Paul McCartney berättar för

Ray Connolly samtidigt som fotografen tar en av många bilder.

som vill diskutera tv-filmen ’Magical Mystery Tour’.

’Magical Mystery Tour’ var tänkt att visas även i svensk tv!

Radiotjänst, som sedermera blev Sveriges Radio, planerade faktiskt att sända filmen i svensk tv någon gång under jul- och nyårshelgen 1967/1968. Men den dåliga kritiken som kom fram i Engelska tidningar så snart filmen hade visats den 26 december 1967, gjorde att Sveriges Radio ställde in sändningen. I samband med att Sveriges Radio delades upp i fyra olika programbolag den 1 juli 1979 blev TV-verksamheterna inom SR ett eget bolag – Sveriges Television Aktiebolag (SVT) – med ansvar för televisionen. Tanken var nog att sända programmet i svartvitt, eftersom det var första den 1 april 1970 som man officiellt började bedriva regelbundna sändningar med sex färgtimmar i veckan.

Dock visades filmen till slut även i svensk tv, men det var först 2012 – 45 år efter det att filmen hade premiär!

Ringo Starr & Paul McCartney still going strong!

Helt fantastiskt att historien kan upprepa sig efter 60 år

På översta bilden ser vi Ringo Starr och Paul McCartney i aktion under en av deras många framträdanden 1964.

Därunder, 60 år senare, ser vi samma herrar spelandes tillsammans i O2 Arena i London den 19 december 2024. Ett extraordinärt minne från året som bara har fem dagar kvar innan vi tecknar 2025.

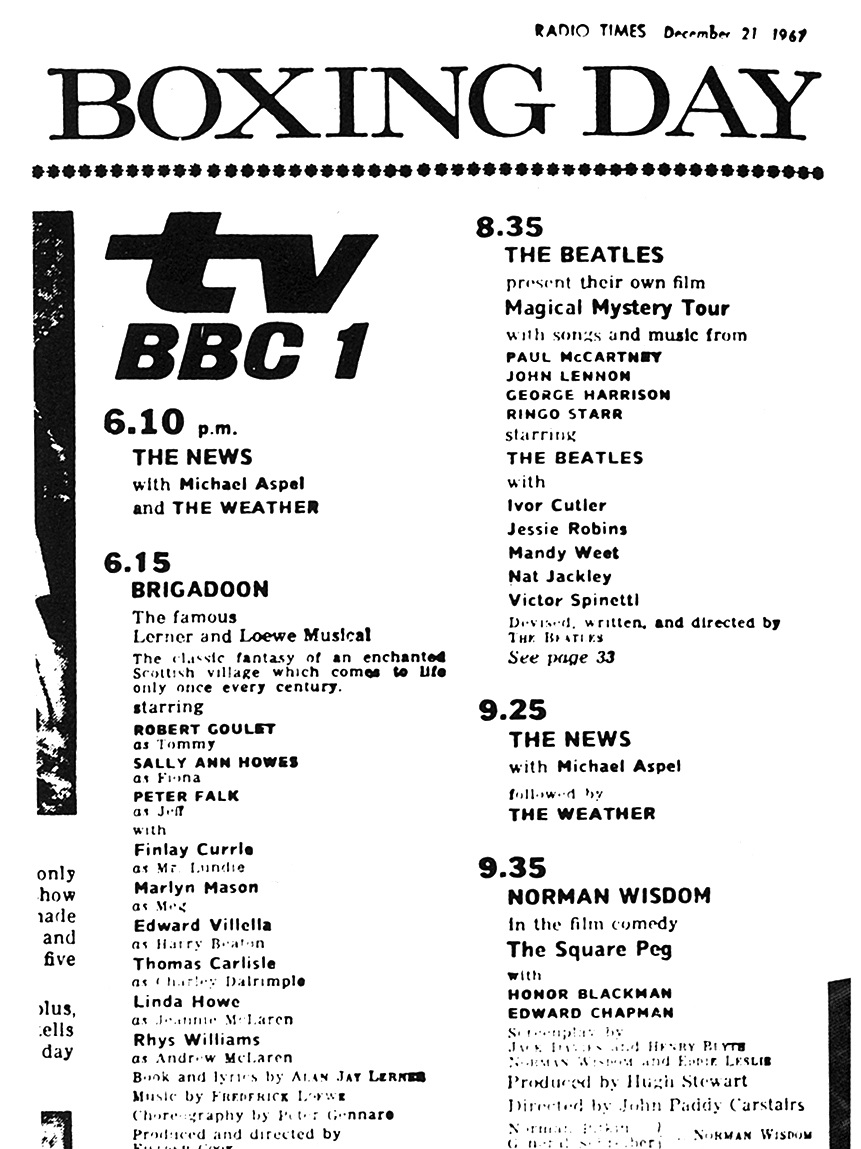

The Beatles – Detta händer den 26 december 1967

’Magical Mystery Tour’ har premiär på BBC 1

’Magical Mystery Tour’ hade världspremiär på tv-kanalen BBC1 med start kl. 20.35.

It was shown on BBC1 on Boxing Day, which is traditionally music hall and Bruce Forsyth and Jimmy Tarbuck time. Now we had this very stoned show on, just when everyone’s getting over Christmas. I think a few people were surprised. The critics certainly had a field day and said, ‘Oh, disaster, disaster!’

Trots att filmen var inspelad i färg , visades den i svartvitt. BBC1 hade inte möjlighet att sända program i färg. Dessutom var det inte så många som hade skaffat sig färg-tv. Hur som helst blev tittarna förbryllade över filmens olika sekvenser och tv-kritikerna sågade hela produktionen.

Being British, we thought we’d give it to the BBC, which in those days was the biggest channel, who showed it in black and white. We were stupid and they were stupid. It was hated. They all had their chance to say, ‘They’ve gone too far. Who do they think they are? What does it mean?’ It was like the rock-opera situation: ‘They’re not Beethoven.’ They were still looking for things that made sense, and this was pretty abstract.

It was a crowd of people having a lot of fun with whatever came into mind. It was really slated but, of course, when people started seeing it in colour they realised that it was a lot of fun. In a weird way, I certainly feel it stood the test of time, but I can see that somebody watching it in black and white would lose so much of it – it would make no sense (especially the aerial ballet shot). We sent a guy out filming all over Iceland, and then it was shown in black and white – I mean, what is this? Painted silly clowns and magicians. What does it mean?

Det pressen skrev dagen efter i tidningarna var nästan hotfullt!

The bigger they are, the harder they fall. And what a fall it was… The whole boring saga confirmed a long held suspicion of mine that The Beatles are four rather pleasant young men who have made so much money that they can apparently afford to be contemptuous of the public.

Whoever authorised the showing of the film on BBC 1 should be condemned to a year squatting at the feet of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

The BBC switchboard was overwhelmed last night by people complaining about The Beatles’ film Magical Mystery Tour. Some people protested that the BBC 1 programme was incomprehensible.

En del av kritiken var riktad mot BBC själva, vilka hade betalat £ 10 000 för rättigheterna att visa Magical Mystery Tour. BBC förväntade sig att filmen skulle locka en publik på 20 miljoner tittare, men det blev i själva verket bara 13 miljoner som såg filmen. Och det var en miljon färre tittare än programmet David Frost Christmas Spcecial som sändes innan filmen visades.

It’s a long day’s night since any TV show took the hammering that this Beatles fantasy received by telephone and in print. Take your pick from the words, ‘Rubbish, piffle, chaotic, flop, tasteless, non-sense, emptiness and appalling!’ I watched it. There was precious little magic and the only mystery was how the BBC came to buy it.

Protests from viewers about The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour flooded the switchboard at the BBC Television Centre last night. Mystified viewers also phoned the Daily Mail. The TV critic Peter Black gave his verdict as ‘Appalling!’ BBC TV chiefs will almost certainly hold an inquest on the show at their next programme review meeting next Wednesday. But, BBC executives emphasised last night as criticism poured in: ‘The Beatles made the film – Not the BBC!’ One caller to the Daily Mail said: ‘It was terrible! It was worse than terrible. I watched it in a room together with twenty-five other people, and we were all stunned!’

The Beatles – Detta händer den 25 december 1967

Paul McCartney och Jane Asher förlovar sig

Men som bekant varade inte förlovningen speciellt länge. Förlovningen bröts efter det att Jane hade återkommit från sitt skådespelararbete i Bristol och fann Paul tillsammans med en annan kvinna. Paret försökte att fortsätta sin relation, men den 20 juli 1968 förklarade för BBC att parets förhållande var slut.

McCartney hade fortsatt att dela säng med andra kvinnor under hela deras relation- Han ansåg att det var helt OK eftersom de inte var gifta. Förutom hans otroheter, hade Jane sätt hur Paul hade förändrats efter det att han hade provat på LSD samt att hennes engagemang för sin skådespelarkarriär innebar också att paret ofta var på olika ställen. Efter separation har Jane varit konsistent med att inte diskutera relationen med Paul McCartney offentligt.

Paul gav Jane en diamantring. Jane hade bott rätt länge vid det här laget i Pauls hus. Det måste sägas att hon, precis som Paul, värderade sin självständighet högt och var helt likgiltig inför brudgummens fantastiska inkomst.

Cynthia Lennon:

Så Paul blev den siste av de fyra som knöt den äktenskapliga knuten. Vi visste att det inte var lätt för honom. Han, liksom resten av Beatles, var i denna mening en vanlig gammaldags Liverpudlian, övertygad om att en frus lott var att sitta med barnen, laga middag och vänta på sin man. Jane motsvarade inte detta alls. Hon var på resande fot lika mycket som Paul, och hon levde sitt eget liv. Hon tänkte inte sitta hemma och vänta på Paul, tvärtom, hon kom ofta inte till våra sammankomster när hon var utomlands på sin nästa turné.

Paul McCartney:

Jag har alltid velat dominera Jane. Jag ville att hon skulle sluta jobba helt.

Jane:

Jag vägrade. Jag är uppfostrad med regler enligt vilka jag är skyldig att göra något. Och jag älskar teatern. Jag vill inte ge upp det.

Paul:

Nu förstår jag att det var dumt av mig. Bara ett spel, ett försök att utöva makt.

Vid olika tillfällen insisterade en av dem på att gifta sig, men sedan motsatte sig den andra det. Jane säger att alla problem berodde på Beatles – så fort hon och Paul kom överens skulle något hända med Beatles, och det var det som fick henne att ändra sig. Och Paul tror att hennes teater är skyldig till allt, även om han aldrig var emot att hon skulle ut på en stor amerikansk turné.

Jane:

När jag kom tillbaka fem månader senare. Golvet blev oigenkännligt. Han tog LSD, vilket jag aldrig gjorde. Jag var avundsjuk på den andliga upplevelse han hade med John. Under dagen kom ett femtontal personer till oss. Allt i huset har förändrats, allt har blivit främmande för mig.

The Beatles – Detta händer den 24 december 1967

Ännu en vilodag för The Beatles inför själva julfirandet

Den här söndagen umgicks John Lennon med sin far Alfred Lennon och firade lite jul hemma hos John Lennon i Weybridge.